You might not know it, but at the turn of the 20th Century, bicycle races were bigger than baseball.

You might not know it, but at the turn of the 20th Century, bicycle races were bigger than baseball.

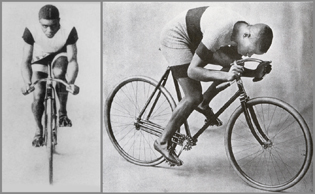

And much like today, the racers were largely White, affluent males. But in 1896, Marshall "Major" Taylor emerged on the track-racing circuit. He would become one of his era's biggest stars, breaking more than 8 world track records and pushing against the era's violent and repressive Jim Crow laws 20 years before Jackie Robinson was even conceived.

Born in 1878, Major Taylor spent much of his adolescence living with a wealthy, White family in Indianapolis. After receiving a bike from his adopted family, the Southards, at the age of 12, Major Taylor soon earned a living performing stunts outside a bike shop, and quickly moving onto competition racing as a young teen.

When "The Colored Cyclone" first hit the track in Indianapolis at age 15, he got himself banned. Not because of bad behavior – Taylor was well-known for his ethics and easy-going demeanor – but because he had the audacity to actually win. He had broken the 1 mile amateur track record.

The persistent racism led Taylor to move to Worcester, Mass., where he enjoys fame and competitions in his name to this day.

Lynne Tolman, a Major Taylor expert and spokesperson for the Major Taylor Association told The Skanner News that she and others are working hard to educate people about Taylor's accomplishments. The association has erected a full-size bronze statue in his honor, holds annual cycling events in his name and also provides teachers a Major Taylor curriculum for use in the classrooms.

Despite overcoming rampant racism in competition – which ranged from threats of violence to being turned away from competitions because of his skin color – and holding multiple world bicycle speed records during his life, Major Taylor's legacy has largely been forgotten.

Tolman thinks it has less to do with the man than the sport.

"Cycling turned into a fringe sport," she says. "It was huge in his day. That changed with the advent of the automobile… and World War I took out a whole generation of young men. It never returned to prominence."

What sets Major Taylor apart from the other racers and athletes of his day – and after – is not only his tremendous physical strength and endurance, but his strength of character, says Tolman.

"It's a tough sport, it's a team sport," she said, in need of mentors, coaches, teammates and opponents who respected your right to be on the track or road. "Major Taylor was utterly alone. They ganged up on him. They'd literally push him into the fences and not even give him a chance."

Despite the hostility he met on many tracks, Taylor met these challenges with "remarkable dignity," says Tolman.

Major Taylor's great granddaughter Karen Donovan says he was a prolific letter writer and diarist, which solidifies his reputation as a gentleman. Donovan told The Skanner News that she spent a lot of time with her grandmother and Major Taylor's only child, Sydney, who spoke often of her champion father.

"I understood Major Taylor held deep, moral values," she said. "He set the bar so high it's a little intimidating."

She says he was raised in a two-family environment. On the weekdays, he spent his time with the Southards, and on the weekends, with his paternal family.

"He probably had a serious conflict," she said. "It certainly had to have an influence. He just wanted to be treated like his White playmates."

Taylor's fairly pristine life has led many in the entertainment business to embellish or outright invent things about his him, Donovan said. She's received a number of film scripts that included scandalous sex and drinking.

"They take so much creative license it's insulting," she said. Others, however, have tried to stick closely to the man's actual story. There hasn't yet been a finished film version of his life, but a website has been set up advertising the film "Major," set to be directed by Kenneth Berris. It is currently in pre-production.

But Donovan says Major Taylor was far from perfect. He wasted much of his winnings on failed investment and business opportunities. In the later years of his life, he became estranged from his wife and daughter, dying largely penniless save for a massive collection of memorabilia. Much of that collection was donated to the Indiana State Museum.

During his youth, though, his accomplishments were worldly. His first professional race was a six-day race of endurance, where competitors rode as many miles as possible in six days and six nights, stopping only for eating and napping. Major Taylor would race for eight miles, sleep for one, and logged 1,732 miles. After his loss, he focused on his sprinting skills to great success.

When White race organizers in the South barred him from the tracks, his hopes at a U.S. championship were sidelined for several years. He set the standing-start 1-mile record at age 19 at 1 minute 41 seconds. He'd later knock that down to 1 minute 19 seconds. While those records no longer stand, there is considerable argument among cycling circles about the role that new technology plays in reaching faster and faster speeds (the un-paced world record is held by Sam Whittingham, who hit 82.33 miles an hour. With a special vehicle to cut wind resistance down to zero, Fred Rompelberg reached 167 mph using just the power of his two feet in 1995 at the Bonneville Salt Flats).

But in his day, Major Taylor was a force to be reckoned with. He became the American sprint champion in 1900. In 1901, he defeated European champions and then raced across Australia and New Zealand. He retired in 1910 at age 32. He self-published his autobiography, "The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World," in 1929.

Tolman says some promoters pushed the "White vs. Black" aspect of the competition, but Major Taylor didn't overtly turn his success into a political stump speech about race or want to be a spectacle reminiscent of a side show.

"He didn't get on his soapbox during his racing career," Tolman said. "He let his legs do the talking."

ENDURING LEGACY

Every year, the Major Taylor Association holds the George Street Bike Challenge for Major Taylor. It is a steep, two-block sprint where the man himself used to train in Worcester. Racers pedal up the 24 percent grade hill one at time, battling the clock.

Aside from installing the Major Taylor and memorial at the Worcester Public Library, the association is heavily invested in the use of the man's story as an educational tool.

Working with several retired Worcestor public school teachers, Tolman says the association developed a school curriculum designed for grades 3 and 4 and for middle school. She says teachers in 27 states have used the curriculum. While many teachers use the curriculum during Black history month, one teacher uses it March to talk about the importance of good sportsmanship. The curriculum is available for free from the association's website http://www.majortaylorassociation.org/mtcurric.shtml.

Historic and Contemporary Black Bike Racers

Throughout bike history, racers of African descent have graced the world's velodromes and road races. Although not as well-represented in professional bike racing as other sports, they have made significant contributions. There is also a long history of Black bike teams across the U.S. that date back to Major Taylor's era. Here are just a few historic and modern Black racers.

Ali Neffati: Became the first African to compete in the Tour de France -- although he was technically from Arab descent. There has never been a Black African to compete in the Tour. Neffati was a native from Tunisia and that nation's champion. Of the 140 cyclists who started the race, he was not one of the 25 who finished. He began participating in racing circuits in 1908 before being asked to participate in the 1913 Tour de France. He went on to compete in a number of competitions until his retirement in 1930.

Gregory Bauge: French racer who has won a number of European, French national and world championships. In 2009 and 2010, Bauge finished first in Sprint Track at the World Champions in Poland and Denmark. In the 2009 World Championships, Bauge made an amazing recovery after he was bumped by competitor Kevin Sireau, who himself crashed. Bauge began cycling at the age of 9 after finding soccer to be not to his tastes. Watch Bauge on The Skanner's YouTube Channel.

Rashaan Bahati: Races with the SKLZ-Pista Palace cycling team and has won the 2008 USPRO National Criterium Championships. Bahati has never finished outside second place in any of the races he's finished. He runs the Bahati Foundation, which supports underserved youth. It is rumored that a television show will follow his efforts to coach Compton, Calif. youth into cycling.

Erik Saunders: As of 2004, Saunders was team captain of the Ofoto Lombardi's Cycling Team, based in San Francisco, Calif. He's competed and won in dozens of races across America and in Europe. After taking several years off, Saunders broke his collar bone in October of 2010 and according to his website, set his "master pro career" back, a career he was trying to rekindle.

Justin Williams: Despite his young age, 20-year-old Williams has been grabbing up victories in a number of regional circuits, with a first place at the Under 23 National Criterium Championships and won third place at the 2010 USA Cycling U23 Road Nationals.